|

|

|

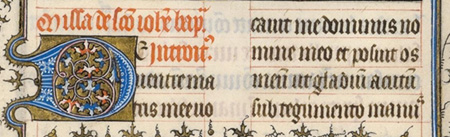

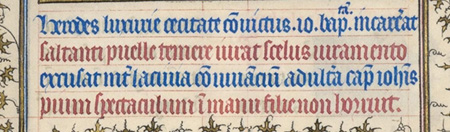

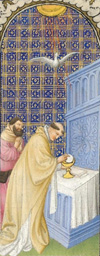

Above: Details of illuminations from Folio 211v, Folio 215r, and Folio 223v from the Belles Heures of Jean de France, duc de Berry, 1405–1408/9. Herman, Paul, and Jean de Limbourg (Franco-Netherlandish, active in France by 1399–1416). French; Made in Paris. Ink, tempera, and gold leaf on vellum; 9 3/8 x 6 5/8 in. (23.8 x 16.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1954 (54.1.1).

We have come to the final section of the Belles Heures manuscript, mainly a small selection of masses. This is a section that sneaks up on you in interest. It first presents as a traditional element—with most of its text in two columns of black ink—but then inserts a few pages in picture-book format. Like the section dedicated to the Penitential Psalms (Folio 66r through Folio 72r), this one starts out with a series of small quarter-page illuminations, but finishes with magnificently accomplished full-page pictures. Finally, it isn’t fully traditional; not all books of hours contain masses, and their inclusion here leads us into interesting questions about Jean de Berry’s use of his prayerbook.

Masses are not one of the essential texts in a traditional book of hours, but may be added as ancillary material. In general, the presence of masses indicates that the individual who commissioned the book of hours was wealthy enough to employ a private confessor or clergy. In this regard, a fifteenth-century chronicler wrote of Jean de Berry: “Animated always by an ardent devotion to the service of God, he maintained in his home many chaplains who day and night sang the praises of God and celebrated mass, and he took care to compliment them whenever the service lasted longer or was more elaborate than usual.” This cautions us against thinking of the duke as commissioning books of hours only for the luscious pictures. They were first and foremost prayer books, and the variety of texts included in the six different books of hours he commissioned is evidence in itself of his employ of private confessors or priests who advised him on his piety and may also have influenced the iconography of illuminations in his manuscripts.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Illuminations from Folio 195r, Folio 198r, Folio 199v, Folio 202r, Folio 204r, Folio 205v, Folio 207v, and Folio 209r

The particular masses included in the Belles Heures start with a sequence of eight highlighting the most important holy days of the year: Christmas (Folio 195r), Easter (Folio 198r), Ascension (Folio 199v), Pentecost (Folio 202r), Trinity Sunday (Folio 204r), Corpus Christi (Folio 205v), and the Exaltation of the Cross (Folio 207v), followed by a votive mass for the Virgin (Folio 209r). Highlighting these key feasts and masses was associated with the French royal Valois family of the duke. The abbreviated texts of the key masses in his prayer book may have helped the duke follow the service, including private masses held just for him, as illustrated in his book of hours called Petites Heures (Paris, BNF, ms. Lat. 18014, fol. 172). All eight of this group of masses in the Belles Heures are introduced by quarter-page illuminations, and despite their small size, several are charmingly detailed, such as the Nativity with the Annunciation to the shepherds in the background (Folio 195r), and the Ascension (Folio 199v), with Christ disappearing into the clouds. The way Christ’s feet dangle from the clouds as he disappears had been traditional iconography in Anglo-Saxon art since around the year 1000, although the inclusion of Christ’s footprints remaining on the mountaintop is a Gothic element.

After the first eight masses there is a dramatic shift in the Belles Heures. The last four masses have a strikingly different heft, beginning with the Mass for the Nativity of Saint John the Baptist, which is preceded by four full-page illuminations. Of those four full illuminations, we can surmise that only the last one—an image of Herod’s feast, in which Salome presents the head of John the Baptist (Folio 212v)—was originally intended to be included. The text on this page is written in two columns of black ink—the format of the traditional sections of the manuscript, including the other masses in this section—and it identifies it as a mass beginning with the Introit prayer.

Detail of text from Folio 212v

However, the three immediately preceding pages have text in single-column blue and red, and that text narrates elements of the story of Saint John, rather than prayers.

Detail of text from Folio 212r

So as we saw with the Heraclius section that was inserted into the Suffrages, the three extra illuminations about John appear to be expansions of the original plan, and perhaps the inception of the added picture cycles in the manuscript.

Illumination from Folio 211r

Let’s step back to discuss the illuminations themselves. The first of the John pictures, on Folio 211r, shows him in the wilderness holding a lamb, flanked by two unidentified men, another of the iconographic mysteries in the manuscript. The page is accorded a broad band border of vine scroll inside the usual leafy rinceaux, the broad band seemingly indicating the start of a section. (For more about the significance of page borders, see “The Hours of the Virgin,” March 24, 2010.)

Illumination from Folio 211v

Next is the baptism of Christ (Folio 211v), notable for the transparency of the water streaming over Jesus’s semi-nude body, and the even more transparent wisp of drape around his loins. The composition is also pleasing, with the curve of mountain and angel’s wings mirroring one another and forming a mandorla around Christ.

Illumination from Folio 212r

When John is decapitated (Folio 212r), the emphasis on blood recalls some of the martyrdoms from the Suffrages, while the elegant Salome, waiting with her silver salver to hold the head, is the picture of fashion in her ermine-lined pink gown.

Illumination from Folio 212v

Finally (Folio 212v), Salome presents the bleeding head at the feast, precipitating Herod’s horrified reaction. His wife Herodias appears to poke the head with a knife, a reference to a famous relic of the saint that had a hole near the eye. Jean de Berry would have seen the relic at Amiens, and copies of that relic, including the wound above the brow, were widely circulated.

Illumination from Folio 215r

The change in the character of the masses section that begins with the John cycle does not end there. Each of the five final illuminations in the manuscript is not only full page but also richly detailed, beautifully composed, and expertly executed. The first two accompany a mass for Saints Peter and Paul, the apostles. The text is the mass—prayer, not narrative—in black, not blue and red, yet the illuminations are unusual story pictures from the life and death of the saints. Folio 215r shows the saints debunking a false magician: Simon Magus falls from the top of the tower as the devils that were supporting him flee at the command of Peter, seen at lower right in yellow with his keys dangling.

Illumination from Folio 215v

The martyrdom scene that follows, with Paul’s head already slashed from his body, includes the detail of two little puddles, recalling a legend that Paul’s head bounced twice, and springs arose on the spots (Folio 215v). Although an executioner raises his sword, Peter’s death is not explicit. Perhaps the courtier whispering in the emperor’s ear is identifying Peter as non-Roman and therefore ineligible for death by the sword, the reason for his martyrdom by inverted crucifixion.

Illumination from Folio 218r

The illumination for the Mass for All Saints (Folio 218r) is unlike all others in the manuscript, a rigorously composed devotional work of great beauty. One could imagine this composition blown up to the scale of an altarpiece in a cathedral. The treatment of the tender Virgin and Child in the center is so intimate and sensitive, but it is enshrined in an array of glory and monumentality. Cherubs and seraphs support the medallion containing the Virgin, while the dove of the Holy Spirit hovers above, weightless between the Virgin and God the father above. The four largest saints are John the Evangelist and John the Baptist, above, and Paul and Peter, flanking the Virgin. Below are the virgin martyrs, Catherine with her wheel prominent among them. The group of male saints behind Peter and Paul is remarkable in the way the figures overlap to suggest depth and quantity, with only the rims of their halos showing to indicate their number.

Illumination from Folio 221r

The last mass is that for All Souls, and the image accompanying it is another stunner (Folio 221r). It shows an empty coffin for the requiem for All Souls, but looks like a funeral in a church, the most common image in most books of hours for the Office of the Dead. Typical as the scene is, its execution displays the incredible virtuosity of the Limbourgs. In the exhibition, we have blown up a photograph of this illumination to wall size, which only makes more obvious how much detail is packed into such a small compass here. We have a sense of the monumental cathedral in which the scene takes place and peek inside one corner of it to see the detailed choir stalls and praying monks. Above, light seems to be transmitted through the leaded windows. Every tiny flame on each candle is painted with multiple colors, suggesting their flicker.

Illumination from Folio 223v

Finally we come to the last illumination in this glorious manuscript, the image of the duke on a journey (Folio 223v), accompanied by the text of a prayer for safe travel. We can well imagine the duke fervently reciting such a prayer, for around the time in which the Belles Heures was created, one of his nephews assassinated another one, and his French royal family was split into either side of a civil war. At the same time, France was also in the midst of the Hundred Years’ War with England. Travel among the duke’s seventeen residences can hardly have been safe. Jean de Berry had this prayer for safe travel added to three of the books of hours he commissioned, along with scenes of himself and his entourage traveling. He is here on the far right in a red cloak and mounted on a beautiful caparisoned white steed. It is fitting that the manuscript closes with an image of the great patron who commissioned it and who was so involved in its creation.

While this is the last section of the manuscript, it is not the final week of this blog, which will include one more post, next week. The last day of the exhibition is Sunday, June 13, so if you can, come see it in person. See it again if you have already come, and if you look closely I guarantee you will see something you missed before. Next week I will give a final tour, on Wednesday, June 9, at 2:00 p.m. Meet me at the entrance to the exhibition.

—Wendy A. Stein

Sources:

Kortweg, Anne S. “The Form and Content of Jean de Berry’s Books of Hours,” in The Limbourg Brothers, Nijmegen Masters at the French Court, 1400–1416, Nijmegen: Ludion, 2005.

Manion, Margaret M. “Art and Devotion: The Prayer-books of Jean de Berry,” in Medieval Texts and Images: Studies of Manuscripts from the Middle Ages. Edited by Margaret M. Manion and Bernard J. Muir. Sydney: Craftsman House, 1991.

Schapiro, Meyer. “The Image of the Disappearing Christ,” in Late Antique, Early Christian and Medieval Art. New York: Braziller, 1979.